NEW HAVEN – The story of the Wachs family is part Book of Exodus, part Hollywood blockbuster, part thriller with one mystery yet unsolved: what happened to the Nazi officer who helped them escape Vienna after Kristallnacht?

A professor of criminal justice at the University of New Haven, together with a group of his students, have been on the case since last November, when they first learned the story from two of the rescued family members.

Ilie Wacs – the family’s surname went from Wachs to Wacs along their escape route – and his sister, Deborah Strobin, kept their story to themselves until a visit to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in the late ‘90s. Eventually, they would come to write a book about the extraordinary outlines of their rescue.

Alois was head tailor in Moritz Wachs’s tailor shop in the Austrian capital and was a friend of the family. After the Nazi annexation of Austria, Wachs’s business was “Aryanized” and turned over to Alois, who became a member of the Nazi party and an officer in the SS.

On Nov. 9, 1938, Alois visited the Wachses, instructing Moritz to gather the family and stay inside their apartment that night. Ilie, then 11, would later write:

“Alois came to our house. His tone was quite grave, and he convinced Papa that something terrible was going to happen. I could tell it was dangerous for him even to be seen in our home. He told Papa, ‘Gather your family tonight. Tell them to come here. Keep everyone inside. You will not be touched.’

“Our building did not have an elevator, only stone steps. I stood inside the door, and I heard hobnail boots coming up, click, click, click, and click. I heard men’s voices. I heard the boots stop at our door, and then I heard them move on. They never even knocked. We were passed over. We were shielded by Alois. We were saved.”

The family stayed locked indoors for two days, finally emerging to search for food in a devastated city. Alois secured extensions so that they would not have to leave Austria but insisted that they get out by Aug. 31, 1939 – which turned out to be one day before the war officially began. Moritz and Henia fled with their two children, first by train to Italy and then on an Italian ship to Shanghai. The rest of their family would perish in concentration camps.

After the war, the siblings got on with their lives and didn’t even think to find out what had happened to Alois, whose last name they never knew. Ilie received a sponsorship to study art at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, while his parents and sister made their way first to Canada and then to New York. After working for designer Alex Maguy, he was invited to New York by suit and coat maker Philip Magone. In the late ‘60s, Wacs worked for coat maker Originala and began designing suits and coats under his own label in the early ‘70s. His highly successful Ilie Wacs and Wacs Works lines spanned over two decades. Since retiring, Wacs, who lives in New York City, has devoted his time to painting.

Deborah married Ed Strobin and settled in San Francisco. As a renowned philanthropist since the ‘80s, she has been credited with organizing large, high-profile fundraising events, including the first ever HIV-AIDS benefit at Davies Symphony Hall, the city’s first Yves St. Laurent couture fashion show to benefit the San Francisco Symphony, and the largest fundraiser in U.S. history for stem-cell research, in 2006. Strobin also served as the deputy chief of protocol for the city of San Francisco and commissioner of the Public Library Commission.

In 1997, on the occasion of Wacs’s 70th birthday, the two siblings visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. for the first time. In one of the display cases chronicling the Jewish refugee communities in Shanghai, they found a photo of Strobin as a young girl.

“I was the last person who wanted to go to the museum,” says Strobin. “I didn’t want to see my past: all our family died in concentration camps, except for us, and I didn’t want to be reminded.”

Strobin would see herself again, in books about Jewish refugees in China and at a San Francisco exhibit on the same topic. “I never told anyone my background, except that I had lived in China,” she says. “I minimized it; I never wanted to view myself as a victim. We were never interested in writing a book.”

But the memories had begun to resurface and as the two siblings reminisced, they eventually decided to write a book.

In the meantime, Henia died, and Wacs became entrusted with a suitcase stuffed with the family’s wartime documents.

“I wasn’t nostalgic about them. They weren’t the good old days. They were evidence of what had transpired. They were part of the historical record,” he says. “I had a sense of responsibility about them. My mother could never release them, but I could. I decided to contribute the documents to the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. in order to tell the story. I had to bear witness. I had to do that.”

Wacs may not have felt sentimental about the papers, but he understood their physical and psychological power, and their importance in understanding his own past.

“My mother, ‘Mutti,’ thank God, kept every passport, visa, birth certificate, and pass that had ever touched her hand. She had to have them. She couldn’t afford to lose them. Without those papers, we didn’t exist. Without proof that we were allowed to exist, we would have been slaughtered. She remembered the sound of the soldiers demanding, ‘Papers, papers.’ She never destroyed them, even after Papa died.”

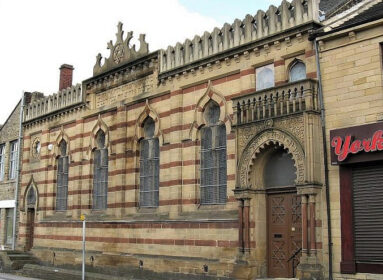

Wacs began to incorporate the documents into his artwork, creating “A Gathering Storm: The Vienna Papers, 1938,” a 15-painting series that debuted in 2004 at the Pamela Williams Gallery in Amagansett, N.Y.

The photo of Deborah Strobin (left) as a young girl that was on exhibit at the Holocaust Museum in Wash., D.C.

In 2011, Wacs and Strobin published An Uncommon Journey: From Vienna to Shanghai to America – A Brother and Sister Escape to Freedom During World War II (Barricade Books). Despite the major role that Alois had played in their personal history, there was little mention of the man.

“I didn’t want to find out what had happened to him; I wanted to maintain the memory of a good German, and I didn’t want to find out that he had become a commander in a concentration camp,” Wacs says.

Strobin, who was two when the family left Vienna, was the one who wanted to know.

“As a child, I always heard my parents talk amongst themselves – ‘If it wasn’t for Alois, we wouldn’t be here’ – but I never understood it,” she recalls. “My brother and I were notorious in continuing things our parents started, so we continued the tradition of not talking about it. I never asked Ilie questions. Only when we started to collaborate on the book did we start to talk.”

After the book was published, the siblings set off on a speaking tour, commissioning Jane Rohman as their publicist. “My first question, after reading the book, was, ‘Where’s Alois?’” Rohman recalls, a query that came up again and again from readers and audience members.

When Rohman visited Wacs at home, where his “Vienna Papers” paintings hang, she suggested that they be shown again publicly. Her colleague arranged an exhibit at the Museum of Tolerance in New York City, to coincide with the 75th anniversary of Kristallnacht, in November 2013.

That is where the University of New Haven (UNH) criminal justice contingent entered the scene.

Before earning a PhD in criminal justice in 2007, David Schroeder worked as a civil and criminal private investigator in Orange County, Calif., where he specialized in civil rights violations and death penalty violations. He was an assistant professor at Western Connecticut State University and an adjunct professor at ASA Technical College and John Jay College of Criminal Justice, both in New York, and joined the UNH faculty in 2008.

Schroeder is the current and third recipient of the Oskar Schindler Humanities Foundation Endowed Professorship, a three-year position established at UNH through a major gift in 2007, in honor of the inauguration of Steven H. Kaplan as the sixth president of the university. An assistant professor of criminal justice, he also serves as an assistant dean in the Henry C. Lee College of Criminal Justice and Forensic Sciences at UNH.

For a decade, he has been a facilitator-trainer at the Museum of Tolerance in New York City, the East Coast education arm of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, and regularly takes groups of UNH students, faculty, and staff to the museum for half-day training sessions.

It was during one such visit last November, that Schroeder and 15 of his criminal justice students met Ilie Wacs. The artist was hanging seven paintings from his collection, “A Gathering Storm: The Vienna Papers, 1938,” inspired by a suitcase full of official documents secured by the Wachs family in order to flee the Nazis. Wacs and Strobin were scheduled to speak at the museum about An Uncommon Journey.

The UNH group walked past the paintings and came to the last piece, a poster describing the story behind the paintings and the request, “Can you help them find Alois?”

“All the students looked at me,” Schroeder recalls. He and his students approached Wacs, who was accompanied by the show’s curator, Mara Williams, and book publicist Jane Rohman.

Schroeder created a spring semester course which he co-taught with Paulette Pepin, associate professor of history and chair of the humanities and social sciences division at UNH. Through Facebook pages in English and German – one of the students, Annika Hocker ’17, is a native German speaker – the group put out a worldwide call for leads, receiving thousands of tips after an Associated Press story about the effort appeared in April. Wacs visited the class in May, to speak with someone who went through that piece of history is much more valuable than just reading about it,” Schroeder says.

Using Austrian, German, and Nazi records, some available online, students have found information about Ilie and Deborah’s father, Moritz Wachs, and the tailor shop he owned. Two of the students, who live near Washington, D.C., have researched records at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and Schroeder has received translation help from an author in Vienna.

Ilie Wacs (front row, center) with University of New Haven criminal justice students and their professor, David Shroeder (back row, center). Shroeder and his students continue their search for “Alois” or his descendants.

The investigation had not been completed by semester’s end, and with half of his class graduating seniors, Schroeder wasn’t sure how the “Finding Alois” campaign would survive. When he asked the students whether anyone would want to continue working over the summer and into the fall, “every hand shot up in the air,” Schroeder says. “When I asked, ‘How long are we going to commit?’ the students said, ‘Until we find him.’”

Then-freshman Isabelle Allen was one of the first students to sign up for the course and is still involved. “I spent a good portion of my eighth grade year studying World War II in English class, and it was one of the most meaningful courses of my junior high school education,” says the Whately, Mass. native. “So, when Dr. Schroeder announced this case, I couldn’t imagine not participating.”

Schroeder says that this inquiry is simultaneously similar to and different from what he encountered as a private investigator.

“The type of case, the scope in historical distance, and the fact that we’re not dealing with anybody who’s a criminal make it different from past cases,” he says. “The techniques we’re using to uncover and vet documents, and reconcile documents with memory are very well-known procedures to me. But the parameters of this particular investigation are unique.”

Allen says that the opportunity to work on such high level research has been an unexpected opportunity.

“Given my somewhat green perspective, this case has been surprising me from the start,” she says. “I am hugely amazed at just how many people we have reached so far. I am also greatly impressed by the tenacity of my fellow students. Being a part of something with such driven people is inspiring. This project provides perspective that is often harder to find in a lot of educational environments. It’s nice to be brought outside the classroom and into the world a bit.”

The class knows that they might not find Alois alive – he would be in his late 90s by now – but hopes to find out whether he had children. “The home run, for us, would be to put Ilie and Deborah in contact with Alois’s descendants.”

Like Wacs, Schroeder recognizes that the investigation may not yield a happy conclusion.

“We have to acknowledge what we’re going to find as opposed to what we’d like to find, and that history is not always made up of pleasant endings,” he says. “The fact that Alois was involved with the Nazi party probably doesn’t bode well in terms of what he may have done later on in the war.”

Wacs, now 87, says that it was the passage of time that changed his mind about finding Alois. “What he did was really an act of heroism,” he says. “He was literally putting his own life on the line and the life of his family because he was a member of the Nazi party. To this day, I’m still amazed by people who did deeds like that. I think Alois deserves a lot of leeway in interpreting what happened afterwards.”

Strobin is hopeful about Alois’s wartime activity. “I have to believe, because of the fact that he saved us, that Alois can’t be a bad guy,” she says. “He took a great risk with his own family, and I have to believe he continued doing that and helped others. It was brave and selfless of him and you want to thank the people who helped.”

Wacs has visited Yad Vashem in Jerusalem only once. He hopes to return soon, to see Alois’s name placed along the Avenue of the Righteous Among the Nations.

To follow the “Finding Alois” case: facebook.com/findingalois.

Comments? cindym@jewishledger.com.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger