By Nadav Shragai

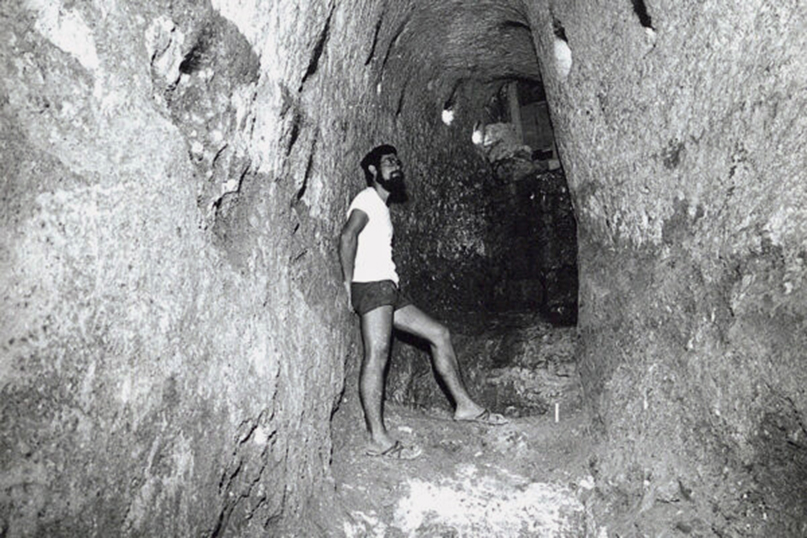

(Israel Hayom via JNS) Like a well-kept secret, the cisterns of the Temple Mount are concealed, barred and padlocked by the Jerusalem Islamic Waqf. In ancient times, the cisterns refreshed pilgrims arriving at the Temple. A few originally functioned as shaft graves or quarries from which stones were carved to build the Temple, filling with water only years later.

According to archaeologists’ calculations, to transport 26,417 gallons of water from the Gihon Spring 2,624 feet to one small cistern on the Mount would have taken at least 1,300 donkey trips. Most of the cisterns on the Mount are considerably bigger, able to contain hundreds of thousands of gallons; water reached them mainly through ancient channels. Rainwater, which was absorbed by the ground of the Temple Mount, also helped fill the cisterns. Research points to the existence of 49 cisterns on the Mount, as well as 42 channels that carried water to them. Some also served as hiding places prior to the destruction of the Second Temple.

While the Temple has been destroyed, the cisterns remain, and can help tell its story and the story of its ruin, which we mark today, July 18, Tisha B’av. The vast majority appear to be empty. A few have been equipped with sensors and alarms. Even Israel’s security forces can only approach most of the cisterns in rare emergency situations. Members of the outlawed Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement even had a plan to refill the cisterns with water imported from Mecca to make the compound more sacred to Muslims.

Only by walking around the Mount is it possible to get a more tangible impression of the cisterns. For years, I would visit two of them. The first, which dates back to the First Temple, has been locked for 10 years and is not part of the guided tours of the area. Its entrance was uncovered in 2012, between paving stones of a Herodian-era drainage ditch that links Siloam Pool to the southern wall of the Temple Mount.

(Hadas Parush/Flash90)

The walls of the large cistern are covered in yellowish-brown plaster characteristic of the First Temple period. The discovery of the cistern challenged the established belief that in the First Temple era Jerusalem’s only water source has been the Gihon Spring. The cistern branches out toward the east, toward the Temple Mount compound, near the location of the Museum of Islam. But that part is blocked, like the rest of the cisterns.

The other cistern I’ve visited lies a little more to the north and does not enter the Temple Mount. Archaeologist Eli Shukron, who discovered both cisterns, thinks that it was a hiding place for a family that lived in the city 2,000 years ago, and that they ate their last meals there, fearing that the rebels would steal their food.

Josephus Flavius’ book “The Jewish War” describes how in the weeks prior to the destruction of the Temple, the rebels would ambush the population of Jerusalem and murder and torture women, children and the elderly as part of their great food theft. The finds at the bottom of the cistern correspond chillingly with Josephus’s narrative. Pottery vessels containing traces of food were found there, along with a small clay lamp that would have provided only enough light to allow the family to see their food without being discovered.

A new book by journalist and Temple Mount researcher Arnon Segal, “Habayit” (“The Home”), attempts to create a “virtual” visit to the cisterns. Segal, who has been writing a weekly column about the Temple Mount in Makor Rishon for the last 10 years, devotes a sizable portion of his book to the Temple Mount cisterns.

His documentation goes back to the golden age of research on the cisterns in the 19th century.

Segal explained that at that time, “Jerusalem was a weakened, sleepy city, far from the awareness of the world and the bloody conflicts that characterized the focus on it starting in the 20th century. In short–a paradise for the research pioneers. This is why most of the information about the cisterns we have in the 21st century is based, oddly, on the sketches [by] people in the 19th century, mainly the findings of Charles Warren and Conrad Schick, two of the most diligent mappers of that century.”

But Warren and Schick weren’t the only ones. Ermete Pierotti, an engineering officer in the Sardinian Army who arrived in Jerusalem after being chosen to serve as a consultant on refurbishments to the Temple Mount, was another.

Pierotti was appointed city engineer by the Ottoman governor of the city, and since he handled the city’s water systems, the mysteries of the Temple Mount were open to him.

Pierotti’s encounter with the “Well of Souls” that was supposedly dug beneath the Dome of the Rock is one of his more intriguing ones, mainly because even now it is unclear whether or not that cistern actually exists.

Q: What is the Well of Souls?

Segal: In the Foundation Stone, there is a cave carved out to which 14 steps lead down, and there is a large marble slab set on its floor that supposedly covers the cistern. Because according to Islamic tradition, the marble slab covers the opening to hell and the souls of the dead buried under it, it was called the ‘Well of Souls.’ The Muslims avoid opening it. The Muslim tradition about that cistern draws on the power of the Jewish tradition of the Foundation Stone, which midrashim say is the foundation of the world. Our sages see the Foundation Stone as a kind of stopper that closes the chasm underneath it, lest it come back and inundate the world like the ancient flood.

Q: And Pierotti went inside?

A: Not even he was allowed to open the marble slab that seals the cistern. He got in through a side opening.

Q: And what did he find?

A: Pierotti wrote that he found a large space, and if he was exact, this is of major significance, because the cave under the Dome of the Rock is full of important Jewish history. According to the main approach [of] Jewish sages, which Maimonides among others espoused, in the time of the First Temple, the Ark of the Covenant was stored in a ‘deep and twisting concealment’ beneath the Holy of Holies. According to tradition, as well as numerous researchers, the Holy of Holies is located where the Dome of Rock is today. Unless he was making things up, Pierotti effectively identified the existence of a major underground space at the Well of Souls, a space that until then had been considered the stuff of legend.

Security officials took pictures

The Well of Souls has made headlines twice in the past decade. The first time, in the spring of 2015, was when the Waqf replaced the rugs at the Dome of the Rock and in the cave beneath the Foundation Stone. This exposed the floor of the structure, and it was photographed. One of the photographs shows the marble slab that might cover the opening to the Well of Souls.

The second time was in 2017, after the Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement carried out a terrorist shooting at the Temple Mount compound that left two police officers dead. The police closed the area off and conducted careful sweeps to ensure that no other weapons were hidden on the Mount. A large contingent of police and Border Police raided the offices of Temple Mount employees, sent ropes down cisterns that hadn’t been opened since the 19th century, and surveyed numerous structures.

Some of the cisterns were photographed, and security officials shared their documentation with the Israel Antiquities Authority. The Waqf claimed that forces had also searched the cave under the Dome of the Rock. Was the marble slab opened? No security officials are volunteering an answer. In any case, the Well of Souls is only one of the 49 cisterns research has identified on the Mount. Researcher Rivka Goren has identified four cisterns as primitive shaft graves, of the kind used to bury the dead until the end of the third millennium BCE, long before the Temple Mount was built.

Another cistern, No. 8, known as the “Great Cistern,” is the largest and can hold more than three million gallons. It was documented and illustrated by William Simpson in 1872.

“Benjamin Mazar claimed that it was a cistern mentioned in Jewish sources that was used as a main water source by pilgrims in the days of the Temple,” said Segal. “According to Mazar, the daughter of Nehunya, who was in charge of supplying water to pilgrims in the Second Temple Era, might have fallen into it.”

Segal points out that Dutch archaeologist Leen Ritmeyer believes that the Great Cistern was also one of the sources of the stone used to build the Temple. “He thinks that most of the large cisterns on the Temple Mount started out as underground quarries, and only after the quarrying stopped were they plastered and used to collect water,” he says.

Segal raises a few more interesting questions about the cisterns: Is Cistern No. 5, at the south of the Mount, the one dug in the Second Temple Period that provided water to Ezra, as researcher Ben Zion Luria believed? The Mishnah says that the curtain that separates the “Holy” from the “Holy of Holies” was submerged in this cistern, and professor Joseph Patrich of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Institute of Archaeology thinks it provided water for the bath where the priests would wash the feet and hands of pilgrims.

Another intriguing one is No. 11, named after the Hellenistic Acra fortress, which Simon the Hasmonean destroyed. The Acra, hated by the Jews of Jerusalem, was designed to force them to worship pagan gods in the heart of the Temple. Researcher Joshua Schwartz was the first to link the Acra to the cistern, but it is not a certainty.

“Most Israelis,” said Segal, “Know the Temple Mount as a place of tensions and conflict. They remember it exists only when the constant conflict that envelops it flares up. But the Temple Mount can be so much more than that, and tell a story that is far beyond the current conflict, a story that exposes the earliest roots of the Jewish people, and hope for its future.”

Nadav Shragai is a veteran Israeli journalist.

This article first appeared in Israel Hayom.

Main Photo: “The Cave Beneath the Holy Rock, Jerusalem” by Carl Haag, 1859. Pencil and watercolor on paper. (Wikimedia Commons)

Why is support for ‘freedom of worship for Jews’ on the Temple Mount so controversial?

By Jonathan S. Tobin

(JNS) Whatever motivated Prime Minister Naftali Bennett to speak of Israeli security forces and police acting to maintain order on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount after Arab disturbances while also “maintaining freedom of worship for Jews” at the sacred site, it was a first.

Bennett’s statement, made on Tisha B’Av (July 18, 2021)—the day on the Jewish calendar that commemorates the destruction of both the First and Second Temples that existed on the Mount—was an eye-opener for a number of reasons. But it came in the context of what appears to be a shift in policy by the new government in that, for the first time since the city was unified in 1967, it is acknowledging that Jews are being allowed to pray at the holiest place in Judaism.

After an illegal Jordanian occupation that lasted from 1948 to 1967, Israel took control of the Temple Mount when it unified Jerusalem during the Six-Day War. Israeli rule meant that for the first time in its modern history, there was complete freedom of worship at all the holy places in Jerusalem. Prior to 1948, the British—and before them, the Turks—had maintained a status quo that established Jews as second-class citizens with respect to prayer at many holy places. During the Jordanian occupation, Jews were forbidden to pray at the Western Wall, let alone the Temple Mount.

But the one exception to that rule after June 1967 was on the Temple Mount where Jews were, in theory, allowed to visit, but forbidden to pray. Then Minister of Defense Moshe Dayan decided, in a gesture intended to help keep the peace, to allow the Muslim Waqf to maintain control over the Temple Mount. Those Jews who did visit were often harassed by Arabs, including police, who were vigilant against any behavior that might be construed as prayer.

That was a policy that was not challenged by any Israeli government.

Dayan’s surrender of the Temple Mount has been criticized bitterly over the years, not least because it allowed the Muslim religious authorities to engage in vandalism on the site when they undertook construction projects that essentially trashed the treasure trove of historical artifacts that existed underneath mosques built on the site of the two temples.

The ban on prayer was maintained because Israeli governments feared that Palestinian Arab leaders would use any gesture towards acknowledging the Mount’s holiness to Jews, as well as to the Muslims who worshipped at the mosques there, to justify violence. Since the beginning of the conflict a century ago, leaders such as Haj Amin el-Husseini, the pro-Nazi Mufti of Jerusalem, PLO leader Yasser Arafat and his successor Mahmoud Abbas have attempted to gin up violence and hate by claiming that the Jews are planning to blow up the mosques.

Palestinians have consistently treated any acknowledgment of Jewish rights to the Mount as an intolerable insult to all of Islam—an unreasonable stand that has nevertheless been supported by the rest of the Arab and Muslim world. Even the supposedly “moderate” Abbas hasn’t hesitated to play that card, vowing that the “filthy feet” of Jews would not be allowed to defile Jerusalem’s holy places during the so-called “stabbing intifada” in 2015 and 2016.

This incitement was largely accepted by Netanyahu as a reason to maintain the status quo. He not unreasonably believed that the alternative was a bloody religious conflict that would undermine Israel’s efforts to normalize relations with the rest of the Arab world and provide fodder for the Jewish state’s critics in the West.

That decision was easy to stand by as long as the Israeli public was largely indifferent to Jewish rights on the Mount. That was backed up by the opinion of some in the Orthodox world that held that Jews should stay off the Mount since the exact location of the Temple’s Holy of Holies was unknown and thereby avoid profaning a place that only the High Priest was allowed to enter while it still existed. But in recent years, more support for the rights of Jews to pray on the Mount has been building, especially among the right-wing and religious parties.

It appears that some Jewish prayer has been going on in the last two years. In 2019, there was a report that some Jews were praying aloud there regularly in a minyan conducted openly without police interference. But the abridged informal services being held did not involve participants wearing prayer shawls or tefillin, so it somehow escaped much notice. But once Israel’s Channel 12 news reported the policy shift last month, it was enough to prompt violence from Arabs.

At this point, it remains to be seen what the implications of that shift and Bennet’s public expression of support for “freedom of worship for Jews” on the Mount—words that never passed the lips of Netanyahu during his 12 years in power, despite his being labeled as a hardline right-winger in the international press—will be.

Whatever the cost he must pay for having said those words, Bennett cannot take them back without doing incalculable damage to himself and Israel.

This dispute is dismissed by some as an unnecessary conflict that is harming Israel’s security merely to satisfy the wishes of extremists. But the Palestinian claim that Jews have no rights on the Temple Mount is inextricably linked to their unwillingness to recognize the legitimacy of the Jewish presence and sovereignty anywhere in the country.

That Abbas and his “moderates” claim there were no Temples on the Mount or the historical nature of the Jewish claims to this land isn’t merely rhetoric that enables them to compete with Hamas. It goes to the heart of their long war against Zionism that they still refuse to renounce.

Those who are still trying to pressure Israel to accept a two-state solution that the Palestinian Authority has repeatedly made clear it has no interest in pursuing need to understand that peace can’t be built on the denial of Jewish rights, especially in Jerusalem.

Israel has no desire to interfere with the mosques on the Temple Mount or stop Muslim (or any) worship there. Those who circulate this lie, whether among the Palestinians or their American cheerleaders, like Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), are opponents of peace, not people working for co-existence.

The world’s tolerance for Palestinian intolerance and antisemitism that finds expression in a denial of Jewish rights to the Temple Mount has helped enable the conflict over Israel’s existence to linger on long after it should have been abandoned by its foes. By taking a position on the Temple Mount, Bennett has done something that should have been done by his predecessors decades ago. Having chosen to take a stand on the issue, he dare not retreat from it lest he justify his opponents’ belief that he hasn’t the right stuff to maintain his principles or his government.

Jonathan S. Tobin is editor in chief of JNS—Jewish News Syndicate.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger