Jewish cemeteries are a treasure trove of Jewish history and genealogy, says an expert on the subject.

By Cindy Mindell

Pop quiz: Why do Jews leave pebbles on gravestones when visiting a Jewish cemetery?

According to Rabbi Joshua L. Segal, there are at least 37 explanations for the tradition.

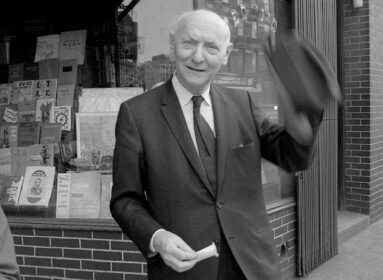

The author of A Field Guide to Visiting a Jewish Cemetery and several other books on Jewish burial sites and markers will cover that topic and many more on Sunday, May 31 at Congregation Beth El in New London.

The son of an Orthodox rabbi and native of Messina, N.Y., Segal earned a PhD in computer engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic University in Troy, N.Y. and started a career with MITRE Corporation and as a certified skiing instructor before enrolling at Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem and Cincinnati.

After his ordination in 1982, Segal served for 30 years as spiritual leader of Congregation Betenu, originally in Nashua, N.H. and now in Amherst, N.H. Along the way, he became one of the country’s foremost experts on Jewish cemeteries, especially in the Northeast. A resident of Bennington, N.H. and still an avid skier (skikabbalah.com), Segal is an officer of the Association for Gravestone Studies.

He spoke with the Ledger about what every Jew should know about the communal institution deemed even more important than the synagogue.

Q: How did you develop an interest in cemeteries?

A: It started when I was a kid. Our synagogue in Messina, N.Y. was an old Congregational church and when the church moved across the street, they couldn’t take the graveyard with them. On Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur when my buns got numb during the long service, I would go outside and walk around the cemetery, and see all kinds of interesting markers. I didn’t know much about them but they were obviously from the 19th century. The cemetery was pretty well full; there were really no burials after the mid-’50s, and you’d see row upon row of children’s markers from the nineteen-teens, from the big flu epidemic, and it was just a very interesting place. My interest at that point kind of went dormant until 1998, when my mother passed away and I had to make a marker for her. I did what a good Jewish boy does: I looked for books on making markers and there were none. There was a vacuum there, so I walked in.

I initially wrote A Field Guide to Visiting a Jewish Cemetery, which is probably not my best book but it’s the one that I lucked out on. My wife told me, “Who do you think is going to buy this after you give away 100 copies to your best friends?” The next thing I knew, the genealogists found the book and it’s now in its fourth printing. The Field Guide is written from the perspective of, ‘I’m visiting a Jewish cemetery; what will I see when I get there and what does it all mean?’

Q: Why do Jews need the Field Guide?

A: In a world where so many times synagogue life is isolated from the rest of one’s life, the idea of going to a Jewish museum means going to Boston or New York City when there is this amazing Jewish museum right in your own backyard. I used to take my post-bar mitzvah classes to the cemetery, and had developed a method called “Monuments 101,” where, if somebody knows the aleph-bet, they can decode most of the Hebrew on 75 percent of all cemetery markers in about 10 minutes. There’s history there, and genealogy, and interesting markers.

Q: How have the inscriptions on American Jewish gravestones changed over the years?

A: We’ve gone through phases. If you go back to Jewish markers from the mid-19th century and earlier, there were long inscriptions and epitaphs and acrostics. You can always find exceptions to the rule, but by the mid-1900s Jewish markers, like markers in most non-Jewish cemeteries, had become what I call name, rank, and serial number: English name, Hebrew name, date of birth, date of death, Hebrew date of death, and the five-letter Hebrew acronym that’s at the bottom of most tombstones: tav nun tzadi bet hay, ‘Let his or her soul be bound up in the bonds of eternal life’ – essentially about Jewish immortality; the Jewish guarantee of eternal life.

All of a sudden, by the 1960s and 1970s, we’re starting to see biblical and secular quotations showing up on markers, and then by the 1990s, you’re starting to see humor show up on markers. There’s one I found in New Jersey: “Old accountants never die; they just lose their figures.” My theory is that people are living great lives by this time. Life is not the hard life of the shtetls of Europe or the sweatshops of New York, and people are going to cemeteries, on some level, to reflect on the person who lived and who they knew. It’s not a somber experience to weep and mourn; it’s literally a celebration of the person who’s buried there.

In Reform cemeteries, I’m seeing a huge return to Hebrew. There was a time when you could go into a Reform cemetery and the only way you could identify the marker as a Jewish one might have been by a Jewish Star on top. In Conservative cemeteries, you’re seeing more material on the markers, some of it in Hebrew. In Orthodox cemeteries, we’re starting to see the acrostic showing up again: let’s say the person’s name is Nathan – Natan in Hebrew, spelled nun, tav, nun. The three lines of inscription are set up to begin with each of these three letters, so that the three letters vertically spell out the name of the deceased. Sometimes it’s just the letters of the name; sometimes they’ll include the father’s name and will throw in a little bit more, like verses from a particular psalm.

If you were to trace the trends, in the 19th century, there is lots of Hebrew; the mid-20th century has less in the way of epitaphs; in the late 20th and 21st century, there are much longer inscriptions.

Now that iconography is being done by sandblasting, it’s going wild. There are seven icons that are truly Jewish icons. My wife and I went to check out the cemetery where we will eventually be and we saw iconography like butterflies – generally having to do with a free spirit but nothing to do with Judaism. You never found the family dog or cat on a Jewish marker in a cemetery 50 years ago but you see them all the time now. With laser etching, they can carve whole scenes on cemetery markers; I saw one with the Old Man of the Mountain, the iconic rock formation that recently fell down, and that was and still is the symbol of New Hampshire. I saw another one with a complete skier scene on it, obviously a representation of the deceased going down the mountain. You have people now who have their entire image carved on the markers and you find that in Orthodox cemeteries too. I always thought that was curious because it seems to violate the prohibition against using graven images.

Back 100 years ago, with photography and the ability to put cameo photos in cemeteries became common, you would see those a lot. They disappeared from popularity by the 1950s, and they’re coming back again now; you’re seeing them especially on the graves of the Russian Jews.

Q: Why do some Orthodox Jews make pilgrimages to the gravesites of celebrated rabbis?

A: The marker on the graves of these tzaddikim is often called ohel – Hebrew for “tent” – or hoisel, which means “little house” in Yiddish. They are covered structures, and to those who don’t know what they are, are often mistaken for a mausoleum. The difference is that, in a mausoleum, the coffins are above ground, and are usually in a drawer or a vault. With an ohel, there is a tent structure and almost a congregating space inside, with a door, but the bodies are beneath the ground. People will assemble, you’ll often find small notes the same way you’d find at the Kotel, with prayers on them.

Technically, as far as I understand, this is a violation of a precept in Leviticus that says not to ask the dead to intercede on your behalf. What you’re doing is asking for the hod avot, the merit of your fathers or your ancestors by asking a tzaddik to intercede on your behalf with God, almost the way non-Jews would use an angel. It’s not proper, in my opinion, but the fact that you see it done all the time is indicative that it is, relatively speaking, a common practice.

One of the most well-known sites is in Uman, Ukraine, where Rabbi Nachman of Breslev is buried, where the Breslovers make pilgrimages. In Everett, outside Boston, there’s a magnificent ohel of Yaakov Yisroel Korff, one of Boston’s great rabbis.

Q: What are the most important things a visitor to a Jewish cemetery needs to know and/or do?

A: If you’re going to visit a Jewish cemetery, and you’re going to visit a specific tombstone, there are probably five things to remember. First of all, don’t walk over the area where the person is buried, and usually the rows are fairly well demarcated so that you can walk between the graves, and that’s just kavod hamet, honoring the person who’s there.

The most common question I’m asked is, “What’s the deal with pebbles on the marker?” The Field Guide has an article in the appendix, not written by me, that gives 37 different reasons for leaving pebbles on markers. The most common one that’s quoted is that, since the Jewish concept of immortality is how we’re remembered by the living after we’ve passed out of this world is to tell the next person visiting the cemetery that this person has not been forgotten – somebody’s been here and they left a pebble to tell everybody that. What’s interesting about this is, as much as Jews have copied marker forms and styles from the non-Jewish world, pebbles on markers are becoming ubiquitous. You’re seeing them in non-Jewish cemeteries too, on non-Jewish tombstones.

As a genealogist, you get an extra generation of people on Jewish markers because most Jewish markers have the names of the parents, at least the father, and now the Reform and most Conservative congregations are including the mother’s Hebrew name too. So you get another generation’s worth of information, which genealogists really like to have access to.

Upon leaving the cemetery, it’s generally considered appropriate to rinse one’s hands off. Some of the better-managed, larger cemeteries that have an office on site will have a fountain to wash your hands at. Most will have at least a spigot by the entrance. This is not cleaning hands but is a ritual purification, like mikvah. The best example I have is what happens when you put water on the Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz. The idea is that there’s a special energy within cemeteries and this, to some extent, removes it as you leave the cemetery.

While one is not supposed to say prayers in the cemetery, there are two that are appropriate, usually a psalm. If I happen to be there and I know somebody who is walking by, I’ll offer to recite El malei rachamim [the traditional Jewish funeral prayer], and most people are happy to have that.

“The Jewish Cemetery: An Owner’s Manual” with Rabbi Joshua L. Segal: Sunday, May 31, 10:30 a.m.-12 noon, Congregation Beth El, 660 Ocean Ave., New London. For information: (860) 442-0418.

For more information on Segal’s books: cemeteryjewish.com.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger