“We have bled – and we belong!” A Hartford Boy Who Went to War

By Rachel Patron

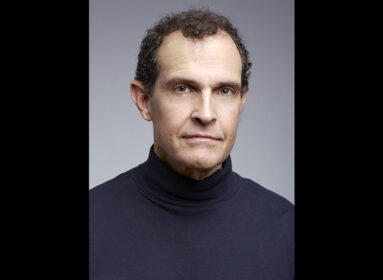

I am the widow of a decorated American POW. My husband, Irving Patronsky, 22, from Hartford, was captured by the Germans on December 16, 1944 – the third day of the Battle of The Bulge – and liberated by the Russians on May 5, 1945.

Irving’s division had trained in England for months following the invasion of Normandy on June 6, though common sense maintained that in these nearly final days of the war, they would not be shipped to mainland Europe. The “Bulge” was a tragic surprise.

How was it possible that after the bloodiest year for Hitler’s Germany, his generals would agree to mount a full-scale offensive doomed to fail from its inception?

Hastily, Irving’s unit was moved from England to Belgium to face the Wehrmacht’s last Panzers. By now the Germans were out of manpower and relied on the remnants of SS troops. Also thrown into the maw of Allied artillery were 13- and 14-year-old Hitler Youth. Not least of all, the once-glorious Panzers were running out of fuel. To compound the misery on both sides, that week of December registered the coldest temperatures since weather statistics had been compiled. Yet, in the short time it lasted, the Battle of the Bulge inflicted severe physical and mental damage on the American boys who fought it – among them my husband Irving.

The events I’m about to recount I had learned only a few years before his death, when dementia had set in and, for someone who had always refused to talk about the war, he suddenly couldn’t stop.

Listen to Irving’s story.

An eerie calm had prevailed over the battlefield. Rumors spread that the SS troops, aware of their doom, were out of control and hysterical, committing war crimes unnatural in combat, even for them. The Americans lay in anticipation, nervous and jittery.

On the second day of the battle, Dec. 14, Irving’s unit was dug into a foxhole, rifles on the ready, and no idea what to do. But they felt that something was about to happen, something bad. It came as a thunderous blast: The German bombardment had begun. On the second blast Irving felt himself covered with warm blood, pieces of flesh and splinters of bone. Surely, he was dying. He started to scream, but no one heard because the universe was filled with fiery booms. As he lay there dying, the sergeant, Leo O’Brien, shook him violently and pointed to his left. That’s when it dawned on him that it was not he who was dying, but the kid next to him who had been blown to shreds. There was so much blood that it had spilled not only on Irving, but on the boy to his right, who sat silently in the dirt, his mouth and eyes wide open, seemingly paralyzed.

Irving cried whenever he told this story:

“I’ve never forgotten the dead boy, though we had not met before the foxhole when we had our helmets on. Later that night, I washed off the blood, but I still dream at night that I’m immersed in it. What bothers me most is that I don’t know what he looked like, because when I looked at him … his face was gone.”

Two days later, on the Dec. 16, Irving’s detail burst into a farmhouse, frozen and hungry. The farmer gave them food and placed a heater nearby. As they were eating, a German patrol was sighted. Quickly, the Americans jumped into the cellar and kept quiet. But the farmer’s family must have betrayed them. The cellar cover sprang open, German rifles pointing at their heads. That’s when my husband’s limited Yiddish vocabulary came in handy. “Shissen zie nicht!” he shouted. “Bitte, shissen zie nicht,” which means: Please, don’t shoot!

The Americans dropped their weapons and were taken prisoner.

When Irving returned home to Hartford he was not yet 23, but no longer a youth. The outward signs were jarring: he was prematurely gray and weighed 100 pounds. The inward scars were more severe: PTSD, nightmares, and bouts of weeping. There was an aversion to taking risks, or to traveling too far away from home.

Irving Patronsky died at age 90, fittingly on Memorial Day 2013, and was saluted by a Marine Honor Guard at the Jewish Cemetery in Avon, Connecticut.

We must always remind ourselves that when danger threatened the country, Jewish boys like Irving Patronsky and his two best Hartford friends, Juky Fegelman and Seymour Nathan, volunteered to defend it.

We must be proud. We have bled – and we belong!

Rachel Patron is a former resident of West Hartford. She lives today in Boca Raton, Florida.

Readers are invited to submit original work on a topic of their choosing to Kolot. Submissions should be sent to judiej@jewishledger.com.

CAP: Irving Patronsky

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger