Three years after his passing, those who knew Elie Wiesel as a friend and mentor reflect on his life and legacy

By Stacey Dresner

NEW YORK –When Nadine Epstein became editor-in-chief and CEO of Moment Magazine in 2004 its co-founder Elie Wiesel became a friend and mentor.

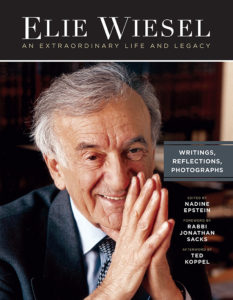

Now, just prior to the third anniversary of Wiesel’s death on July 2, Epstein has published Elie Wiesel: An Extraordinary Life and Legacy – Writings, Reflections, Photographs.

Now, just prior to the third anniversary of Wiesel’s death on July 2, Epstein has published Elie Wiesel: An Extraordinary Life and Legacy – Writings, Reflections, Photographs.

Edited by Epstein, the book includes “A Visual History” of Wiesel that takes the reader from his birth in 1928 in Sighet, Romania, his time as a teenager in Auschwitz, and the publication of Night, his seminal work on his Holocaust experience, to his years as a journalist, professor, Nobel Peace Prize winner and as Rabbi Jonathan Sacks says in his forward, “the leading voice of the survivors of the Holocaust.”

The bulk of the book is made up of reflections about Wiesel from 36 contributors including Michael Berenbaum, founding director of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Philanthropist Ronald Lauder, Natan Sharansky and Oprah Winfrey.

The book also includes more than 100 photos of Wiesel: portraits of him as a solemn young man, family photos, and group shots with well-known colleagues and friends.

Besides her duties at Moment Magazine, Epstein is founder and executive director of the Center for Creative Change and founder of the Daniel Pearl Investigative Journalism Initiative. She has covered politics in the Chicago bureau of the New York Times and at the City News Bureau of Chicago. She was a Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan, holds a B.A. and M.A. in International Relations from the University of Pennsylvania, and was a University Fellow in the political science doctoral program at Columbia University.

Epstein has written several books, contributed to anthology collections and co-written a documentary film that was a semifinalist for the 2001 Academy Awards.

In her introduction to the book, Epstein, who lives in Washington, D.C., says, “We believe that it is critical to keep Elie’s memory alive at a time when antisemitism and prejudice of all kinds in the United States and Europe are once again on the rise and the lessons he taught have been called into question.”

Recently, the Ledger talked to Epstein about her book, her friendship with Elie Wiesel, and how she says he “expanded her universe.”

Wiesel with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir and Josef Rosensaft in Jerusalem at a 1970 commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen.

JEWISH LEDGER (JL): In your introduction to your new book you write, “When you come into the presence of a hero like Elie Wiesel and pay attention, your universe within expands.” How did he help your universe to expand?

NADINE EPSTEIN (NE): When I first met him I had just taken over Moment and I went up to Boston to see him. He was then teaching at Boston University and I walked into this gorgeous, spacious, wood-paneled, book-lined room and he jumped up from behind his desk and said, “What can I do for you?” Every time I talked to him, by the way, he would start the conversation by saying this. It was an incredibly lovely gesture; he was very generous in that way.

Still, I was completely tongue-tied. I felt like I was speaking to a character in Night who was 15 years old and suffering through the Holocaust. It took me a long time to become comfortable enough to be able to see him as a person. Over the years we became friends and we bonded over writing. He was very encouraging of my work at Moment and pushed me to have confidence in and develop my own voice. In the process of writing the book my universe was expanded even further. In talking to other people who knew him I came away with a fuller view of who he was. Understanding another person more deeply, in particular Elie, has helped to enhance my universe.

On Dec. 10 1986, Elie Wiesel received the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway, presented to him by Egil Aarvik (right) chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, as his wife, Marion, and their son, Elisha, looked on.

JL: Did any of the contributors share something about Elie Wiesel that you hadn’t known before – anything that surprised you?

NE: I didn’t go into it with preconceived ideas. Every contributor’s story had its own beauty, its own meaning and its own wrinkles of surprise. Some people said things that managed to capture something in a perfect way, like Jonathan Sacks in the book’s foreword, “Whatever he did and wherever he went, Elie carried within him six million fragments of our people.”

I learned a lot from Natan Sharansky. He talked about how Elie’s most significant legacy was having brought the plight of Soviet Jews in the 1960s to the attention of the world and of the American Jewish community, and how Elie’s book The Jews of Silence helped unify the American Jewish community to take action and succeed in bringing Jews out of the Soviet Union.

I was struck by Jean Bloch Rosensaft’s story. She is the child of survivors and as a young girl, she and her sister and her parents traveled to Israel on a ship. The girls would explore the ship and they would often see this haunted looking man walking the deck. He didn’t say anything to them, but they were scared of him. One day they were walking on deck with their father and their father said, “Elie, Hi! What are you doing here?” and Elie said “Sam!” It turns out they knew each other. This story was a glimpse into Elie’s suffering as a young man. There are more than 100 photographs in the book and it’s reflected the early photos. He doesn’t smile.

Ted Koppel tells a wonderful story in the afterword he wrote for the book. He and Elie were very good friends. Elie was going to speak to his “Nightline” staff at a retreat or something and Ted picked him up at the airport in his car. Ted stops for gas. He gets out of the car, puts the gas in the car, pays, gets back in the car and Elie says to him, “How do you know how to do that?” You learn about another aspect of Elie – that he was a man who didn’t drive or put gas in cars. He inhabited a very intellectual world.

In the reflections of Elie’s cantor, Joseph Maloveny, you’ll learn that Elie had a beautiful voice and that he knew a huge amount about classical music, Jewish liturgical music, and folk music.

Sonari Glinton, who was one of Elie’s students at Boston University, tells this wonderful story about how he was in school on the south side of Chicago, and he was assigned to do a book report. Out of laziness, he chose the shortest book he could find, Night, and it completely transformed his life. He ended up going to school at Boston University because Elie was there. He became Elie’s student and later a journalist because, as he says, Elie taught him to speak out for what he believes. Sonari went on to be the longest serving African American male at NPR.

JL: Why write the book now?

NE: In the book, Father Patrick Desbois [founder of Yahad-In Unum, which locates and documents mass graves of Jews murdered by the Nazis in Eastern Europe] warns that we are in danger of forgetting Elie Wiesel and people like him. I agree. The Holocaust survivor generation is leaving us, and I’m always surprised by how many people have never heard of Elie. In the Jewish world, more people have heard of Elie. They know his name. They know he is somebody they should know about. They may know that he wrote Night, which they may have read. But they often don’t have a deep understanding of who Elie was and what he stood for.

At the dedication ceremonies for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum on April 22, 1993 – Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day: (l to r) Israeli President Chaim Herzog, President Bill Clinton, and Elie Wiesel.

JL: Were you also influenced to write the book by the steep rise in antisemitism in the U.S. and around the world?

NE: Absolutely. The world has changed dramatically since Elie died, which will be three years ago July 2. … It was impossible to foresee that in a few months there would be a newly empowered Far Right in the United States that, which would be whipping up an icy blast of national anti-Jewish sentiment, a kind we hadn’t seen in decades. It was months before neo-Nazis trolled Jews in Whitefish, Montana; before the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville; before the massacre at the Tree of Life synagogue; before the killing at the Chabad service in Poway, California.

Elie missed all this and there is a part of me that’s glad that he did. But then there is another part of me that wishes that he were here because he was a very visible presence, a respected voice in speaking out against prejudice of all kinds. And that’s important to remember – that he spoke out against all kinds of prejudice, all kinds of suffering, all kinds of genocide, even though he felt the Holocaust was a unique kind of evil. And one of his major issues was antisemitism. He had this ability to speak with political leaders, and speak his mind with them in a very graceful, kind of non-ideological way, and he did so with President Reagan during Bitburg.

In 2006, Wiesel and actor and humanitarian activist George Clooney addressed the UN Security Council about the ethnic violence in Darfur.

JL: What impact do you think he would have had if he were alive today?

NE: I think Elie would have been someone who would have commanded the respect of President Trump and members of his administration and he could have been a guide in a positive way. And I think there are some lessons we can learn from him. He had a special touch. He managed throughout most of his life to transcend polarization. He had a way of being able to talk to a lot of different people and part of that was because he had that moral gravity that came with having suffered through the Holocaust; he was someone who had experienced and known evil in its ugliest form.

There were other reasons he could transcend polarization as well. He was able to reach people in ways they understood. He wasn’t an ideologue. He was able to talk to Republicans and Democrats. And while he enjoyed the tumult of cultural, religious, social and political thought, he always wanted that tumult to be tasteful and civil.

So what can we learn from him? We can, as he counseled, not forget, not be indifferent. We can remember to care about all kinds of suffering and take action to combat it. But we can also listen and encourage other voices and we can graciously bend over backwards to be civil in our own discourse. Elie knew too well what would happen when communication and civility break down and evil ascends.

This message is incredibly important for us to hear now, to remember, and to take forward with us and to teach to our children.

CAP: Elie Wiesel and Nadine Epstein

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger