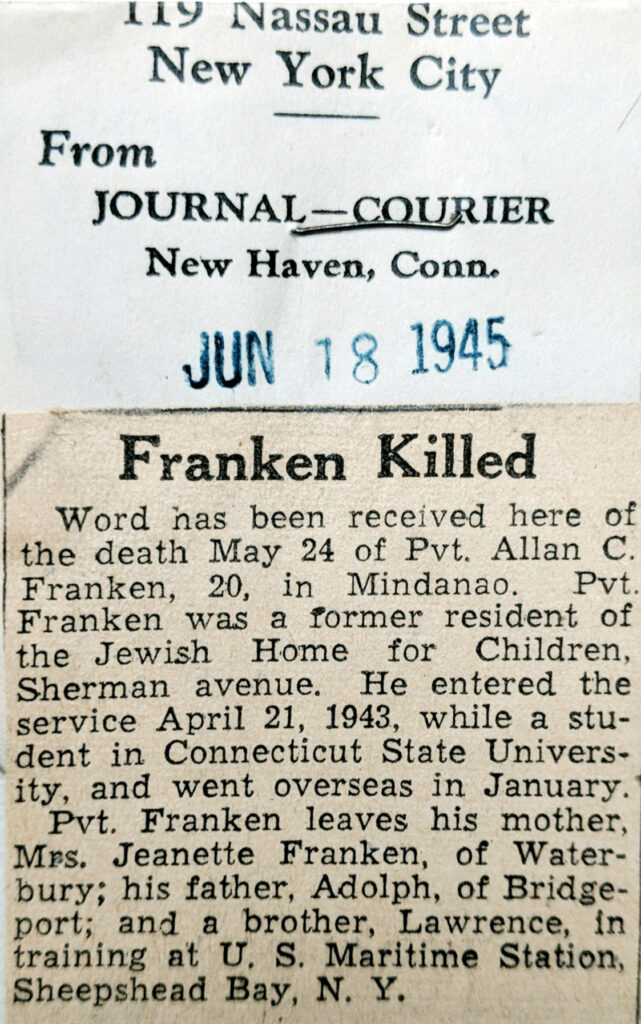

By Rabbi John Franken

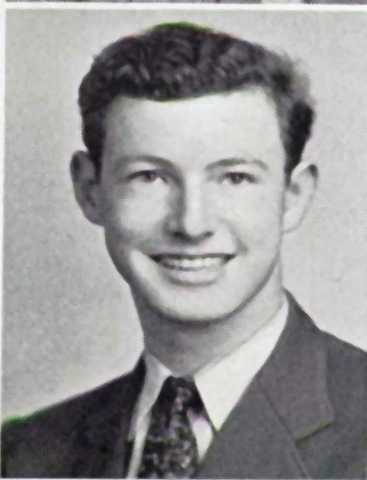

My uncle, Pvt. Allan C. Franken succumbed to face wounds in an army field hospital on May 24, 1945. He was just 20 years old.

Allan was my father’s only sibling. My middle name was given in his memory. I suppose that’s why I grew up wanting to know as much as I could about this uncle I never knew; the father of the cousins I never had; the one with a radiant smile who, out of patriotic duty, had transferred from the U.S. Army Air Corps into the infantry in order to do do “something worthwhile” for the war effort. He served in the 21st Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division.

One thing my father told me I found especially upsetting. In the military cemetery in the Phillipines where Allan had been buried, his grave was marked with a Latin Cross.

If this had upset my father, he never showed it. He seemed to have become reconciled to it, perhaps because he thought nothing could be done about it anyway. So, my father told himself and his family the story that Allan had converted to Christianity during his army service.

Even so, I could never make sense of it. After all, Allan and my father spent much of their childhoods in the New Haven Jewish Home for Children, where they attended Hebrew school daily and Shabbat services weekly, celebrated their b’nai mitzvah, and maintained strong ties with their mother, aunts, uncles and cousins (several of whom were refugees Nazi Germany). Thus, I reasoned, if there was a conversion it must have been for the convenient purpose of avoiding antisemitism in the U.S. Army or concealing his identity if, God forbid, he fell into enemy hands.

Then, in the spring of 2019 the phone rang. On the line was Rabbi David Ellenson who, as president of the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College, had ordained me 16 years before.

David explained that he was calling on behalf of his old friend Rabbi Jacob (“J.J.”) Schachter, a professor at Yeshiva University and a fellow historian. A few years earlier, Schachter was standing inside a Normandy cemetery and wondering why there were relatively few Star of David headstones, since it was well-known that Jews represented 2.7 percent (about 11,000 soldiers) of all U.S. casualties – about 11,000 Jewish soldiers.

Schachter mentioned this to his friend Shalom Lamm and the two men immediately launched their own investigation.

What they found was astonishing: Hundreds of Jewish war dead had mistakenly been buried under the Latin Cross – the symbol of Christianity. David suggested that Uncle Allan was one of them.

I countered weakly with the family lore that somehow Allan had converted, but David explained that the research showed conclusively that Allan had lived and died a Jew. There was no indication of any conversion whatsoever and, crucially, his Jewish status upon death had been confirmed by the Jewish Welfare Board. The strong likelihood was that it was a clerical mistake, committed innocently during the massive effort of burying 17,184 American soldiers who lost their lives in the battlefields of the Philippines and the South Pacific, in the Manila American Military Cemetery.

A few weeks later, thanks to the extraordinary assistance of Lamm and Schacter’s team, I filed an application for a headstone change for Pvt. Allan C. Franken with the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC).

Five months later the application was approved.

On Feb. 12, 2020, I was privileged to attend the solemn ceremony in which the headstones on the graves of my uncle and four other Jewish servicemen buried beneath the cemetery’s graceful, emerald lawns, were lifted and replaced with Star of David headstones inscribed with the names of the five fallen soldiers: 1st Lt. Robert S. Fink of New York; Pvt. Allan C. Franken of Hartford, Conn.; Sgt. Jack Gilbert of New York; Pvt. Arthur Waldman of Detroit and Pvt. Louis Wolf of Philadelphia.

It was one of the most moving and gratifying moments of my life.

“Anyone visiting these cemeteries should recognize that Jews have been part and parcel of America, have been committed to America, have loved America, have volunteered to fight for America – and have made the ultimate sacrifice for America,” said Rabbi Schacter, speaking at the ceremony.

In addition to to Rabbi Schacter, remarks were made by Shalom Lamm, the American Battle Monuments Commission authorities, the American and Israeli ambassadors to the Philippines, and representatives of all five families.

Before his headstone change, I chose to address my uncle directly, declaring this moment the funeral he never had; these words the eulogy he never received; the memorial prayer the words that had never been prayed – all by the nephew he had never met.

Together, it amounted to the restoration of his good name and the redemption of his Jewish identity. It was not just a chesed shel emet (a true kindness shown to the dead by the living), but a chesed v’emet (a kindness and a truth – or, in this case, a repair of the truth).

As I recited the Kaddish and placed a stone on the new Star of David headstone, I felt a sensation that Allan – 75 years after his death – at last could rest in peace.

May 24, 2020 marked the 75th anniversary of my uncle’s tragic and untimely death. May his memory, together with those of all of his brothers and sisters who fell in service of our country, be ever for a blessing.

A New Haven native, John Franken is rabbi of Temple Adas Shalom in Havre de Grace, Maryland. He is a member of the Advisory Board of Operation Benjamin, whose mission is to preserve the memories of American-Jewish men and women who fell in World War II. Learn more at operationbenjamin.org.

About Pvt. Allan Chase Franken

Born in New York, Allan Franken resided on New York’s Upper West Side until age 10. During the Great Depression, the family moved to his mother Jeanette’s hometown of Waterbury.

Pvt. Franken’s ties to Connecticut’s Jewish community run deep.

His great-great uncle, Samuel Zunder, arrived in New Haven in 1850 to serve as the first Jewish clergy for the small German Jewish immigrant community living there. Samuel’s brother, Maier, Allan Frankel’s great-grandfather, came soon afterward and, as president of the New Haven School Board, was instrumental in making New Haven the first major American city to integrate its schools. The Zunder School was later dedicated to him and several articles about him appear in the Jews of New Haven series.

After the Frankel family relocated to Connecticut, Pvt. Frank’s father, Adolph, left to find work but never returned. Because Jeanette had to go to work and neither childcare nor government assistance was available, Allan and his brother Larry were placed in the New Haven Jewish Home for Children. There they resided until age 18. At the Jewish home, the cultural and religious backdrop was entirely Jewish. Religious school was a requirement four afternoons a week. Shabbat services and observance of kosher dietary laws were required. And the Frankel brothers attended Jewish camp each summer in Orange.

He also was regularly visited by his mother, a lifelong Reform Jew, with whom he was always close and who kept his many letters written during his time in the service. Occasionally, Adolph would come to New Haven to take Allan and Larry to Franken family gatherings in New York or Connecticut. A number of their uncles, aunts and cousins were refugees from Nazi Germany, and Allan and Larry were well-acquainted with the antisemitism those relatives had experienced in their hometown of Nuremberg.

After graduating from James Hillhouse High School in 1942, he enrolled in the University of Connecticut to study engineering. His studies were interrupted in 1943 when he entered the U.S. Army, where he first served in the Second Air Force, and then, feeling frustrated at being “pushed around from place to place with no future in sight,” he volunteered for In 1945, he shipped out, and in April 1945 he took part in the Battle of Davao. It was here he sustained machine gun fire to his face and jaw. Evacuated to an Army field hospital, he died of his wounds on May 24, 1945.

Pvt. Frankel was awarded the Purple Heart for his bravery, he is memorialized on the World War II Memorial in Waterbury, where his mother lived.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger