A stunning new exhibit at the Met Cloisters illuminates a medieval Jewish treasure

By Josefin Dolsten

NEW YORK (JTA) — There are few remnants of the once flourishing Jewish community who lived in the Alsatian town of Colmar, France in the 14th century.

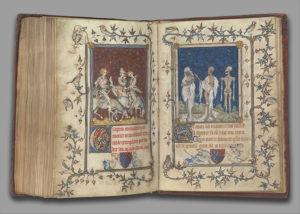

“The Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg.” Its original owner, sister of the Holy Roman Emperor and wife of the future king of France, also died of the plague. The exhibit also includes other illuminated manuscripts, significant objects and Judaica from the Cloisters, the Jewish Theological Seminary and several private collections.

Jews were blamed by their Christian neighbors for the outbreak of the Black Death plague that devastated Europe in 1347-51. Some 300 European Jewish communities were destroyed by rampaging antisemitic mobs. It is believed that as many as 20,000 Jews were murdered, many of them burned at the stake.

A Roman emperor who then controlled the area later seized their assets.

A star and crescent gold ring, 13th-first half of 14th century, from the Colmar Treasure. “The delicacy of the goldsmithing is extraordinary,” says Barbarra Drak Boehm, the show’s curator.

But a few pieces of jewelry that testify to Jewish life in the town miraculously survived after being hidden on a street once called “Rue des Juifs” — Street of Jews — in the walls of a house in Colmar during the 14th century. They remained stashed there for more than 500 years. The items — a cache of jeweled rings, brooches, and coins — were discovered in 1863. They were all the precious possessions of an unknown Jewish family living in medieval Alsace.

Several of these items are now on view at New York’s Met Cloisters museum, part of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibit, “The Colmar Treasure: A Medieval Jewish Legacy,” revives the memory of a once-thriving Jewish community that was scapegoated and put to death in the mid-14th century.

A silver key from the 14th century. It’s significance: Jewish law prohibits carrying money and valuables beyond the household on the Sabbath, as opposed to wearing jewelry, which is allowed. Worn as a brooch, the key would have been used to lock up a box kept at home and filled with significant objects for safeguarding.

On loan from the Musée de Cluny, Paris, the Colmar Treasure is displayed alongside select works from The Met Cloisters and little-known Judaica from collections in the United States (including the Jewish Theological Seminary) and France.

A sapphire gold ring from the second quarter of the 14th century. A Jewish gem merchant writing in Venice in 1403 described sapphires as being “ as luminous as the heavens.” Associated with purity and chastity, the blue stones were prized by wealthy citizens.

Although the objects on view are small in scale and relatively few in number, the ensemble overturns conventional notions of medieval Europe as a monolithic Christian society. The exhibition points to both legacy and loss, underscoring the prominence of the Jewish minority community in the tumultuous 14th century and the perils it faced.

A Jewish ceremonial wedding ring, inscribed “mazel tov,” made of gold and enamel, from the Colmar Treasure, circa 1300-1347.

For Barbarra Drake Boehm, the show’s curator, the exhibit gives voice to a lost community. [“I want to] draw people in so they can see that there is a Jewish medieval legacy,” she told the New York Jewish Week in a recent interview. “…To understand the tragedy of the loss you have to feel something on some kind of gut level. And the Colmar treasure allows you to do that.”

Main Photo: A jeweled silver brooch, second quarter of 14th century.

The Colmar Treasure: A Medieval Jewish Legacy is on view at The Met Cloisters now through January 12, 2020. For more information, visit www.metmuseum.org.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger